IBM Watson

Creating the original avatar for IBM's Jeopardy! Juggernaut

Project Overview

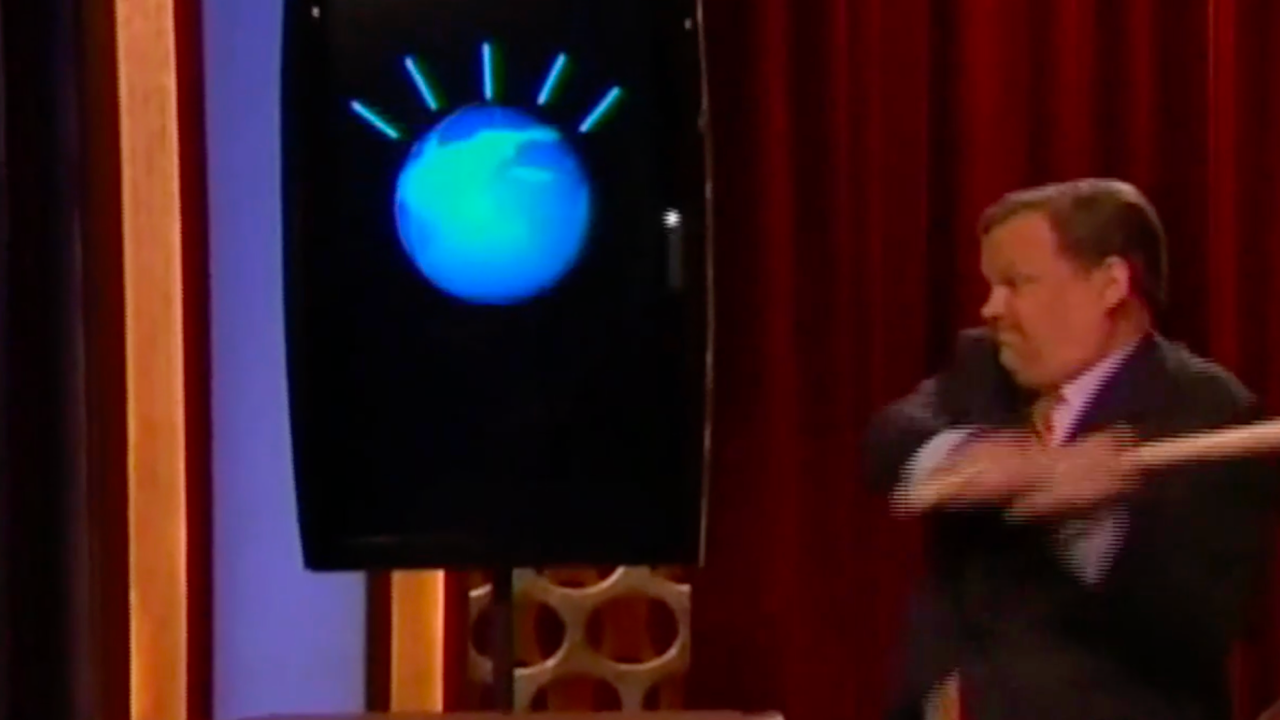

Watson was IBM's groundbreaking artificial intelligence system designed to compete on the quiz show Jeopardy! against human champions. My constribution to the project required creating a visual representation—an avatar—that could serve as Watson's physical presence on the televised competition, transforming a room-sized supercomputer into a relatable on-screen contestant.

The challenge was unique: how do you represent a computational system capable of processing natural language, evaluating thousands of possible answers, and calculating confidence scores in approximately three seconds? The solution needed to communicate complex internal processes while being accessible to millions of viewers. All while maintaining IBM's brand identity and fitting into the existing Jeopardy! stage and broadcast design.

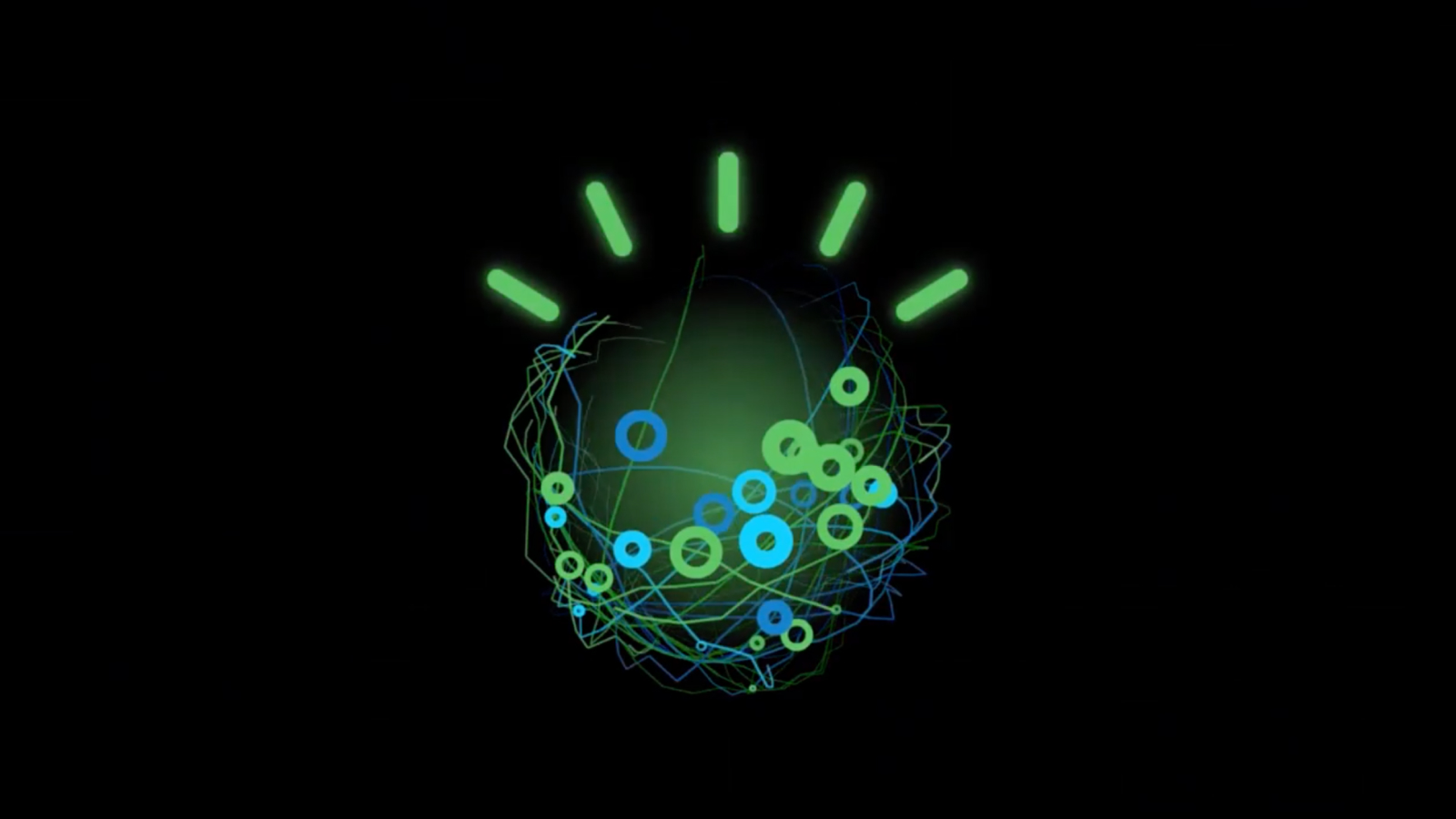

The avatar design centered on a globe form inspired by IBM's 'Smarter Planet' logo (a key component of IBM's global identity at the time), overlaid with 42 dynamic threads representing parallel streams of computation. The number 42 was deliberately chosen as an homage to Douglas Adams' 'The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy,' adding a layer of personality to an otherwise purely technical visualization.

A swarm of particles animated across the globe's surface, with a single 'leader' particle followed by others, creating the visual metaphor of thoughts racing through Watson's processing systems.

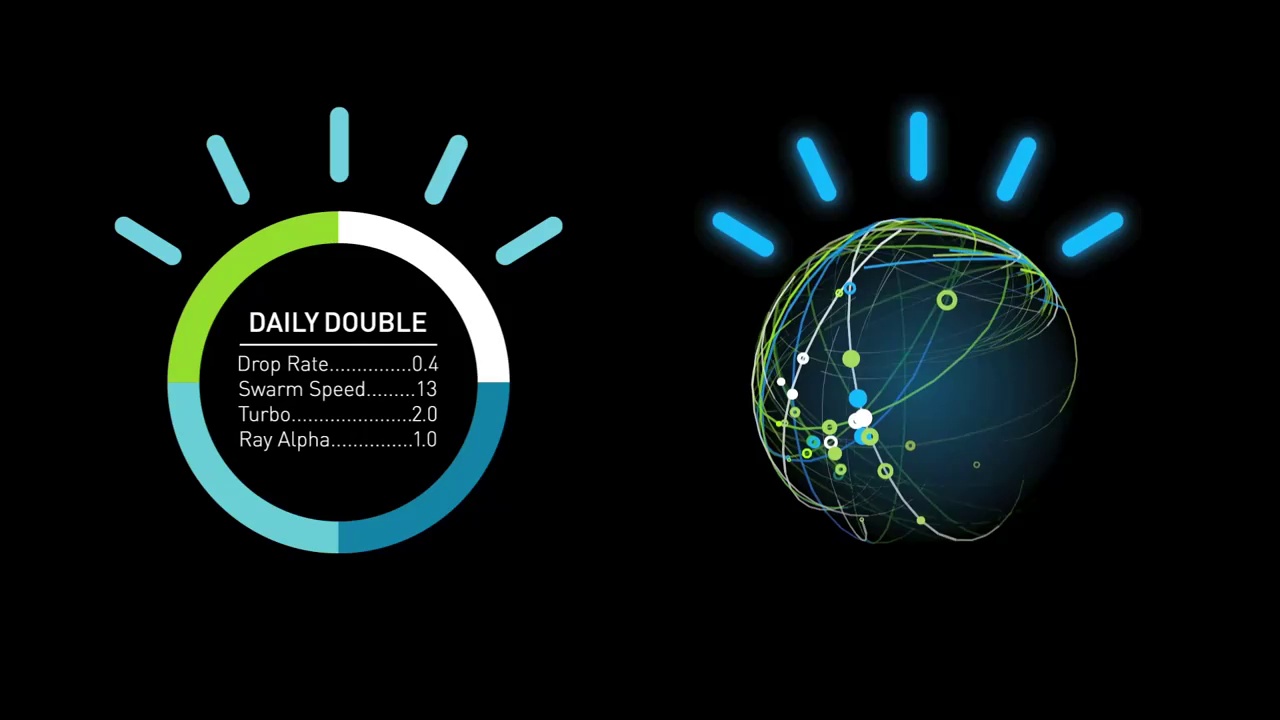

Confidence Visualization System

The avatar incorporated 36 distinct states mapped to Watson's confidence levels and processing stages:

- High Confidence: Particles swarmed to the top of the globe and glowed green

- Low Confidence: Particles migrated to the bottom and glowed orange

- Idle State: Avatar subtly pulsed in IBM brand colors during host dialog and clue reading

- Processing State: Increased particle activity and speed when algorithms were actively analyzing clues

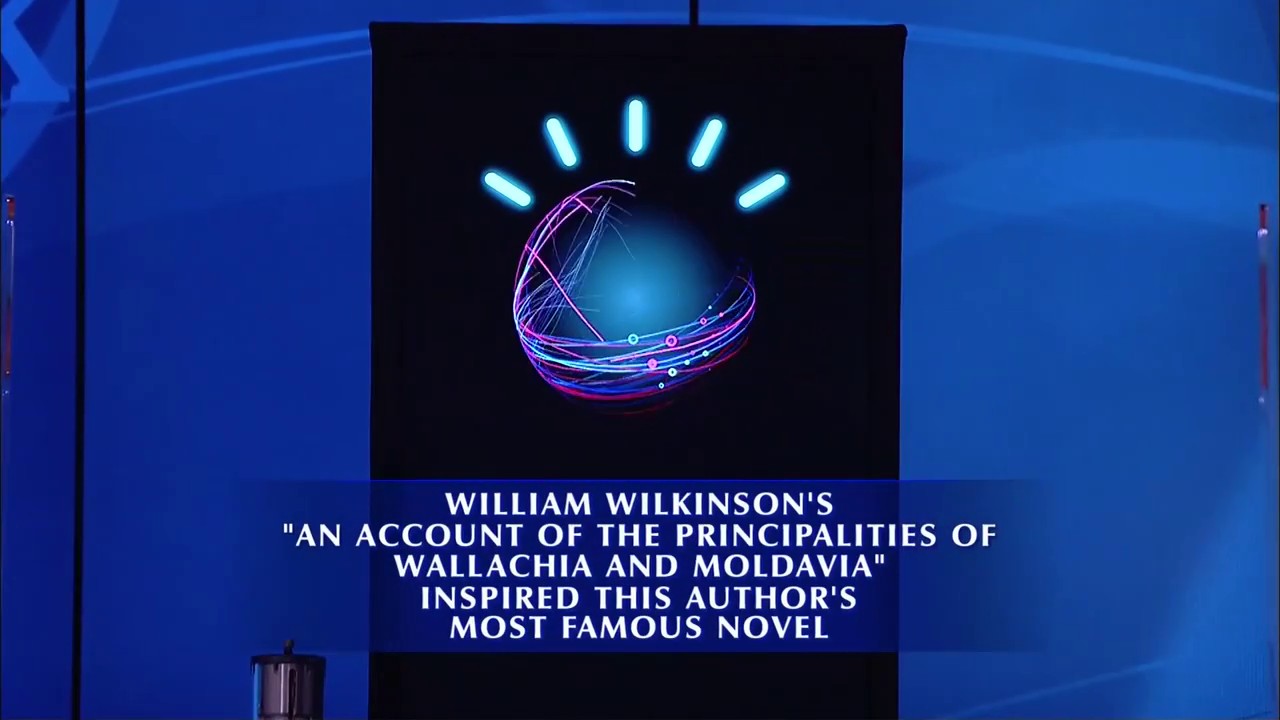

Answer Panel Design

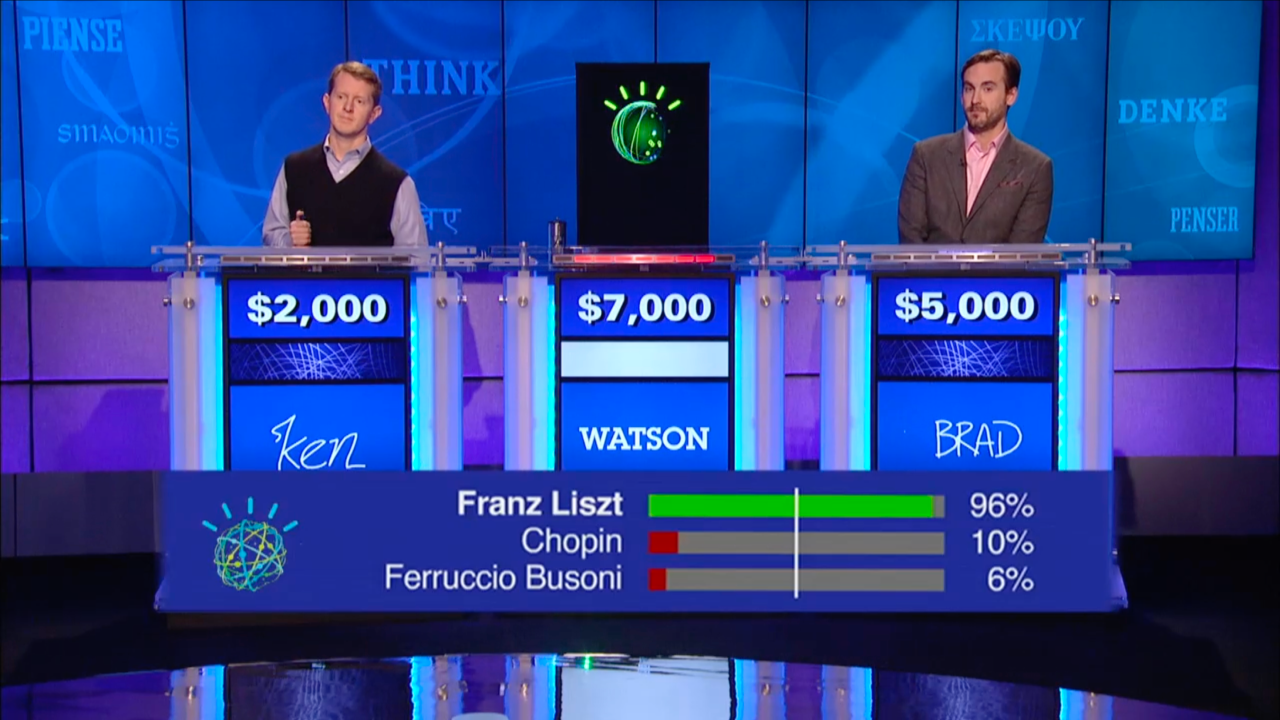

Working with IBM's research team, particularly lead scientist David Ferrucci, we developed an answer panel that displayed Watson's top three response candidates along with confidence percentages and a buzz threshold indicator. This transparency was crucial for demonstrating that Watson wasn't simply guessing but engaging in sophisticated natural language processing and reasoning.

The panel revealed the thousands of potential answers Watson generated for each clue, narrowed down to the most probable three, each with a weighted confidence score. If Watson's confidence exceeded the buzz threshold, the system would trigger the buzzer mechanism to ring in.

Technical Implementation

We implemented the generative design through a middleware system that pulled real-time data from Watson's DeepQA architecture. The system translated data—confidence scores and processing states into color and motion that viewers could intuitively understand.

The avatar ran as a separate visual layer synchronized with Watson's actual responses, creating the illusion that the avatar itself was the computer rather than a representation of the 10 refrigerator-sized server racks located in an adjacent room.

Impact & Results

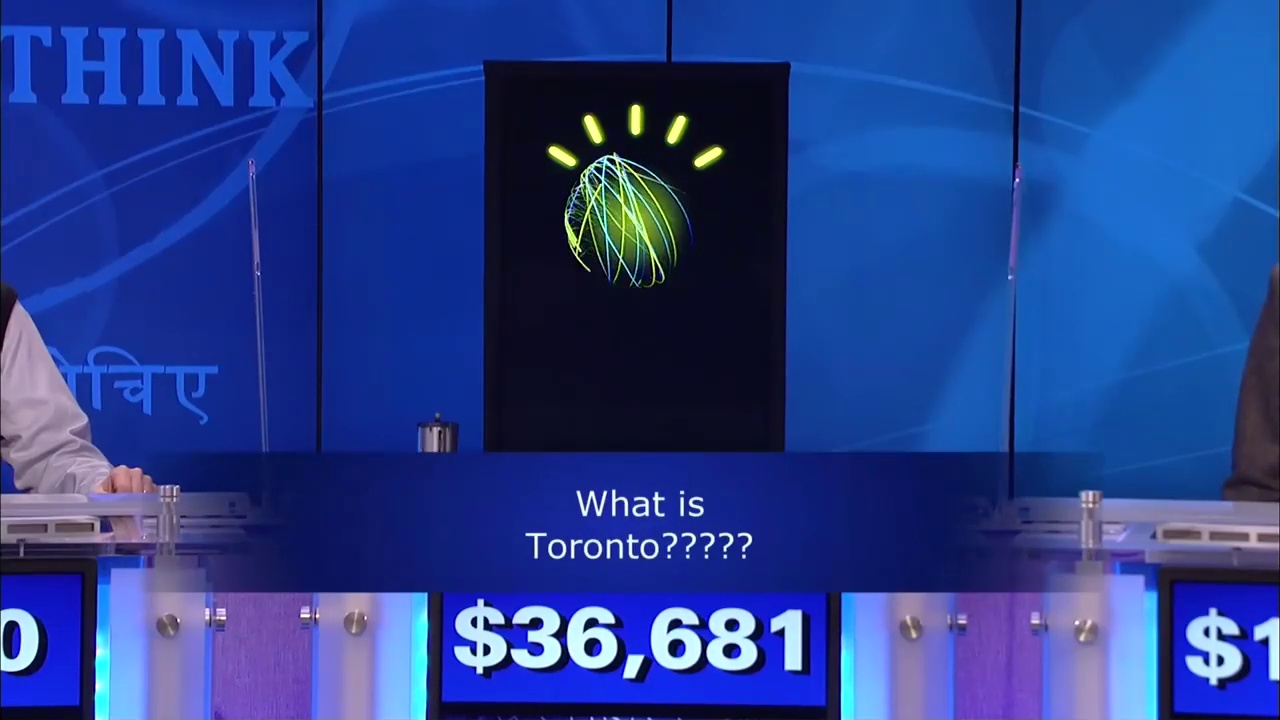

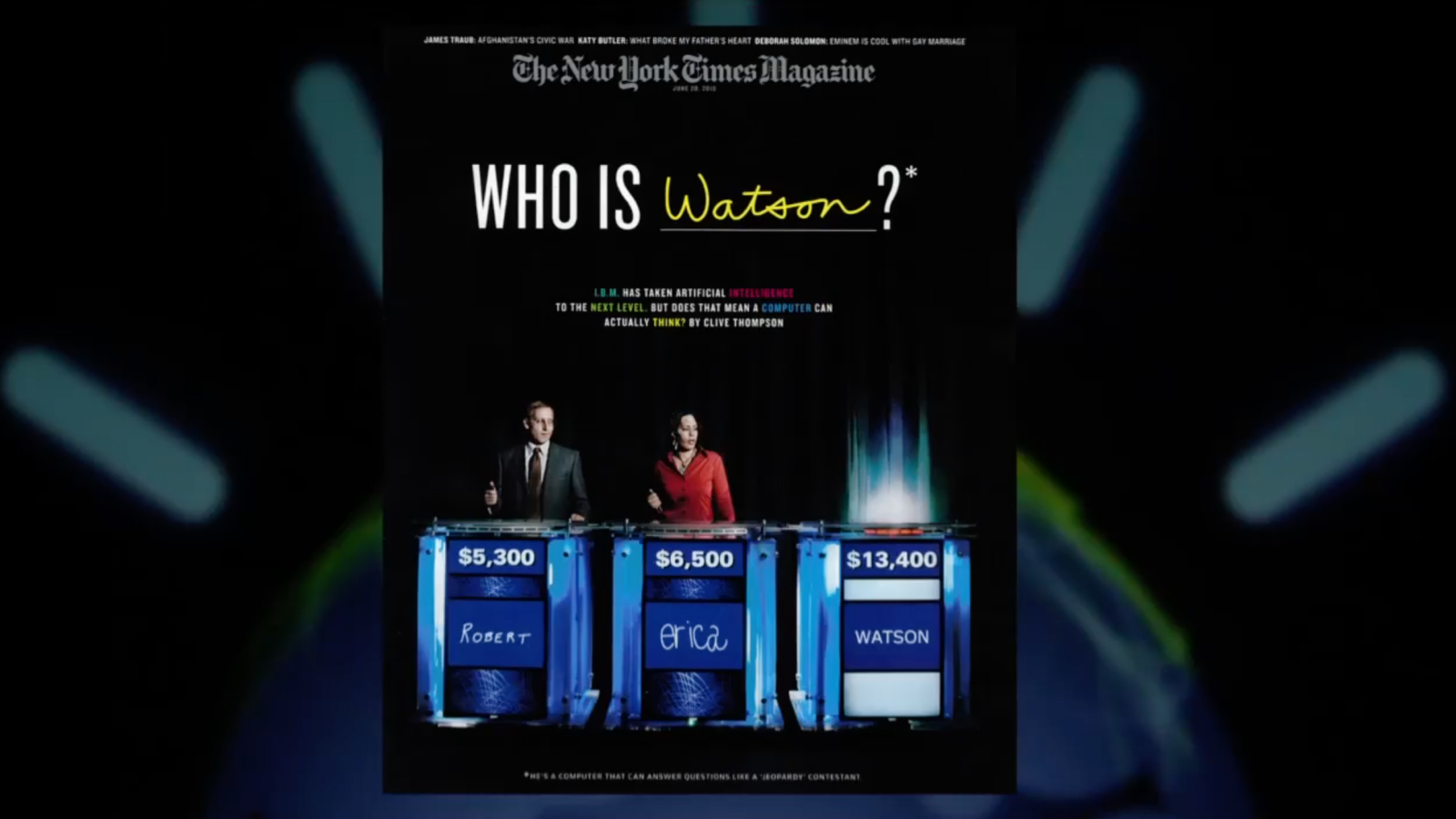

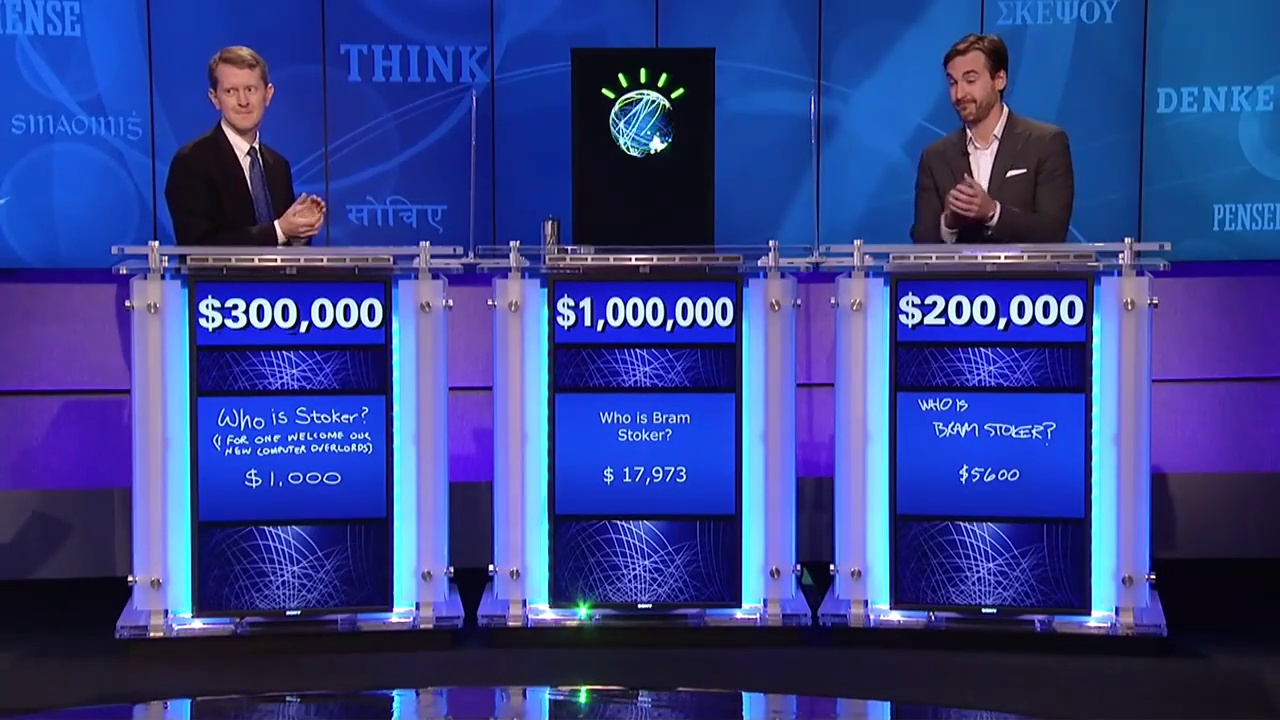

The televised matches aired February 14-16, 2011, becoming a ratings phenomenon and media spectacle. Watson defeated Jeopardy! champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter, winning the $1 million first-place prize.

- Millions of viewers watched the three-day competition, making it one of the most-watched Jeopardy! events

- 40% of viewers said Watson's performance had a positive effect on their opinion of IBM

- Traffic to IBM.com increased by 556% during the Jeopardy! braodcast

- Extensive earned media from shows like Late Night with Conan O'Brien, The Daily Show, and The Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon helped place IBM Watson in popular culture

Cultural Significance

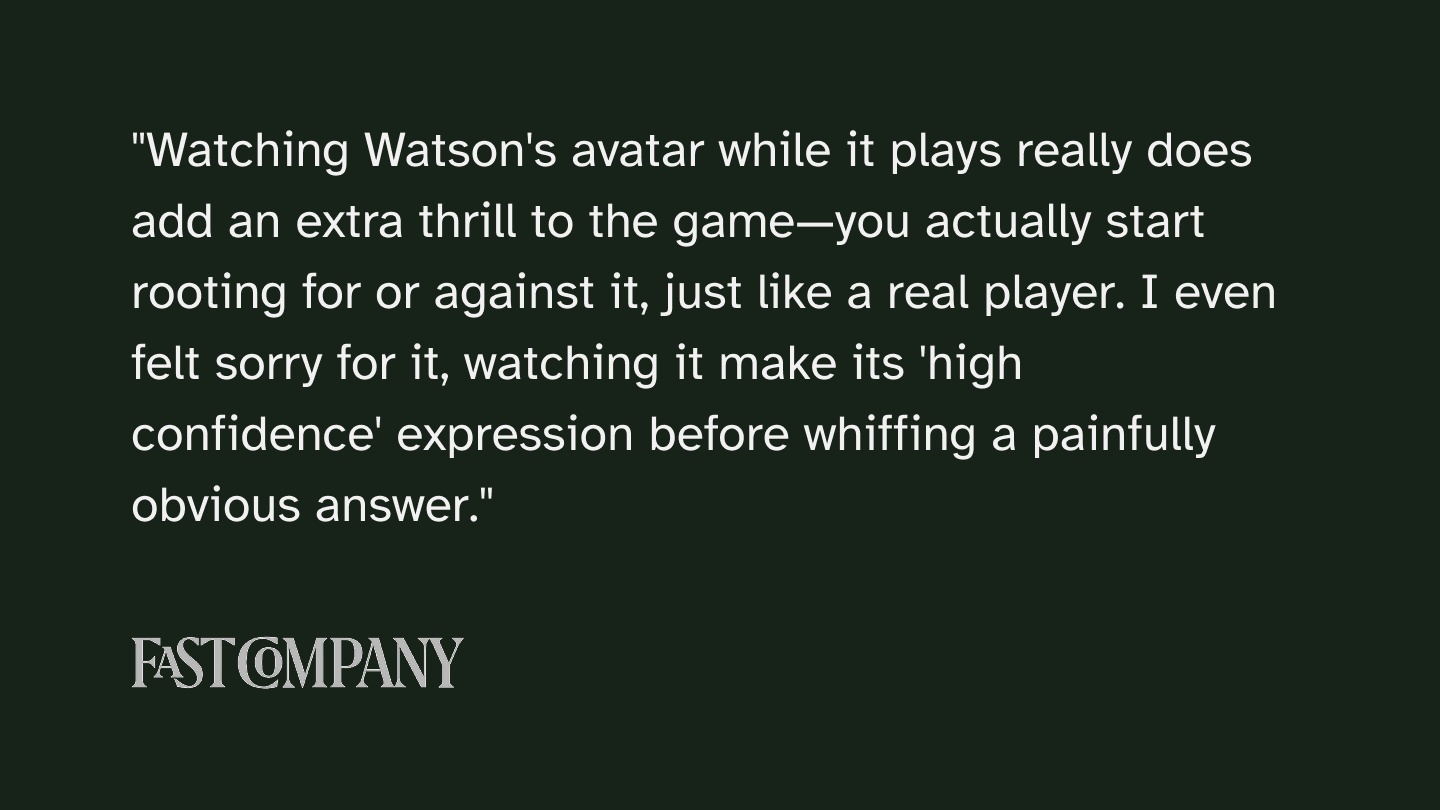

The avatar succeeded in making Watson feel like a participant rather than a machine. Viewers reported emotional responses to the avatar—rooting for or against it, feeling sympathy when it displayed high confidence before missing an answer. This emotional engagement was critical for IBM's broader goal of demonstrating AI as a collaborative tool rather than a cold, calculating replacement for human intelligence.

Key Takeaways

Design Principles

- Abstract over anthropomorphic: Avoiding human features prevented uncanny valley effects while allowing the system to be judged on its actual capabilities

- Data-driven emotion: Color, movement, and spatial positioning translated computational states into intuitive emotional cues

- Transparency builds trust: Showing Watson's confidence levels demonstrated sophisticated reasoning rather than blind computation

- Brand integration: The globe motif reinforced IBM's global Smarter Planet campaign while serving functional visualization needs

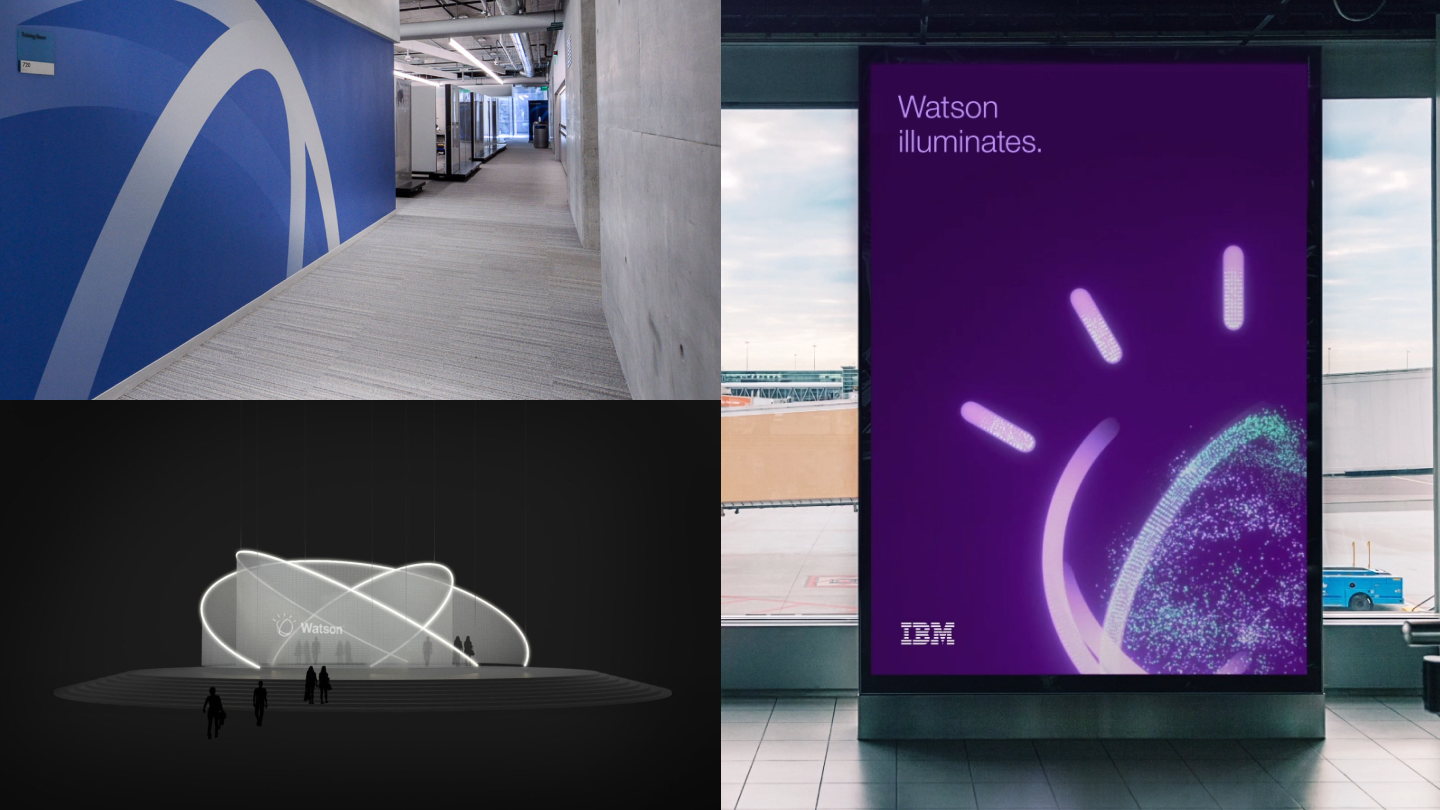

Long-term Legacy of the Avatar

The Watson avatar design established foundational principles for AI visualization within the IBM brand. These principles are still in use today, influencing how IBM Watson systems are represented to customers. It demonstrated that sophisticated technology doesn't require dumbing down—transparency and thoughtful design can make even the most complex systems accessible and engaging.

Technical Overview

- 36 distinct triggerable states

- 42 thought threads visualized

- Real-time data visualization from DeepQA system

- Color-coded confidence mapping (green/orange/blue)

- Particle-based animation system

- Three-answer display panel with confidence percentages

Project Reflections

The Watson avatar project represents a unique convergence of brand design, data visualization, artificial intelligence, and broadcast media. It required balancing multiple stakeholder interests—IBM's marketing objectives, Jeopardy!'s format integrity, the research team's desire for transparency, and viewers' need for comprehensible engagement.

The 18-month development timeline forced iterative refinement, with over 100 practice matches providing real-world testing for the visualization system. Each state needed calibration to accurately reflect Watson's internal processing while remaining visually distinct and meaningful to viewers unfamiliar with natural language processing algorithms.

Perhaps most significantly, the project demonstrated that good design isn't about simplification—it's about translation. The avatar didn't hide Watson's complexity; it made that complexity visible, understandable, and ultimately more impressive to general audiences.